The Most Important Facts About Conventional Farming

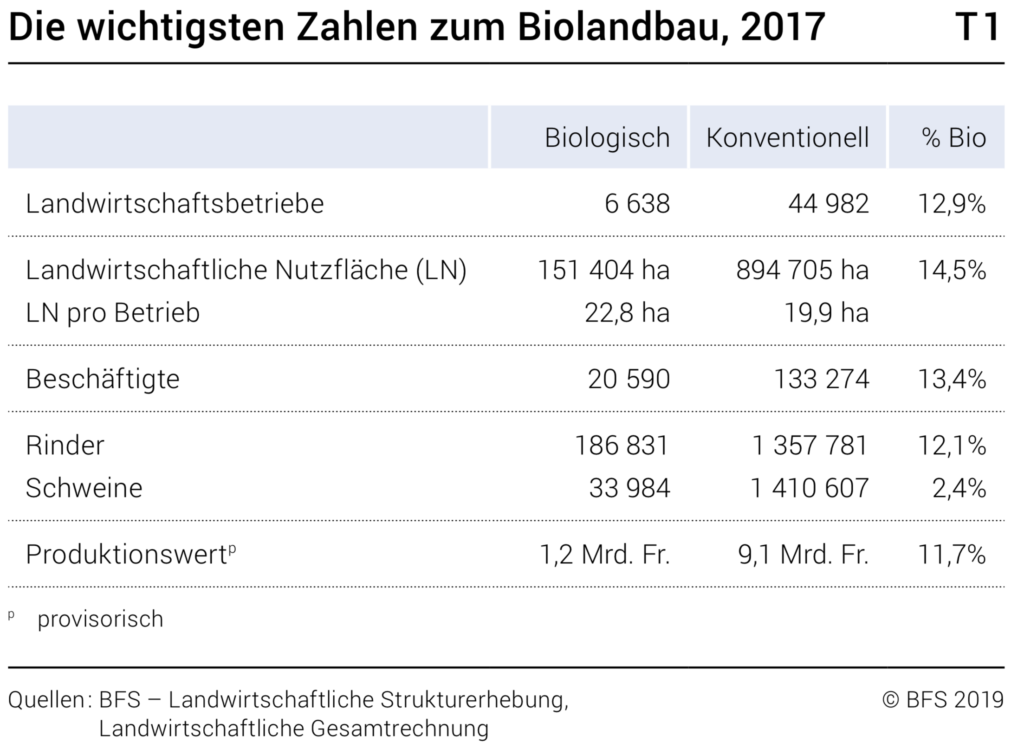

Conventional agriculture produces most of our food. Its guidelines also affect non-human animals. Only 2.4% of the pigs and 12.4% of the cattle that are bred and killed for their flesh originate from farms that meet organic standards.1 The term “conventional animal farming” refers to a form of farming that - in contrast to organic farming - is not tied to specific practices and methods. Farms based on conventional methods comply with minimum legal requirements; e.g. as to how much space a certain animal must have. Since the regulations for conventionally produced flesh, milk or eggs only have to meet the minimum legal requirements, the animals live in confined spaces and have almost no entertainment options.

How do conventionally farmed animals live like in Switzerland? How much space do they have to move? Do the animals have the opportunity to graze or exercise? The following text aims to clarify the minimum requirements for conventional animal farming for cows, calves, pigs and chickens and to comment briefly on them. This research is based on the Swiss Animal Welfare Act.

Why is it important to know how animals live under conventional guidelines? The Swiss Animal Protection asked 1034 people about their assessments of how conventionally kept cattle live like. Only 20% of the people surveyed correctly assessed the real conditions in cattle farming. The remaining 80% mistakenly related Swiss cattle farming to large barns or grazing opportunities.2 As a result, the Swiss meat and dairy industry receives a level of trust that it does not deserve. Furthermore, the distorted ideal of Swiss animal agriculture prevents people from being motivated to address the fact that the exploitation of non-human animals is a morally relevant issue.

Cows and Calves

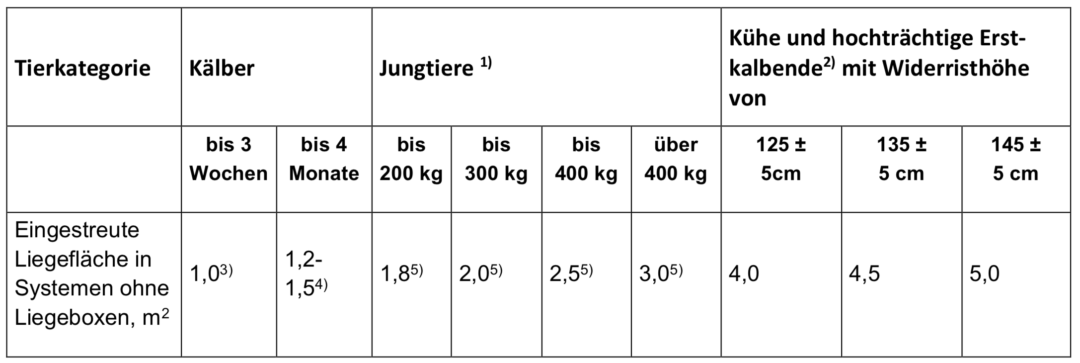

The chart lists the minimum standards for moving and resting areas based on the age and weight of the animals. A calf of 4 months has 1.5 m² of space, cattle weighing over 400 kg get 3m². Contrary to the popular belief, conventionally raised animals do not have the right to graze which means that they often live in a barn their entire lives long. There is also no obligation to provide the bedding area with straw. The Animal Welfare Act only stipulates that cows must be provided with “suitable” bedding such as deformable soft material.3

Another widespread misconception is that calves are allowed to stay together with their mothers for at least some weeks. Conventionally raised calves are separated from their mothers immediately after birth and subsequently isolated in either boxes or calf hutches. Single boxes in which calves up to two weeks old are kept, must compromise an area of 85x130cm, while calf hutches (up to three weeks old calves) must cover 1m² movement space (after this time the calves will live in groups). Calves living in boxes or hutches only have visual contact with other calves - they are not able to move freely or interact with them.4

Image: In order for cows to give milk, they must give birth to a child. There is no use for the young animals, which is why they are ripped from their mother shortly after birth and killed afterwards. The mother cows are then artificially inseminated again. The picture shows calves in hutches at the “Chueweid” animal farm in Drälikon Hünenberg. Approximately 300 cows and 200 calves are living on the farm.

Image: In order for cows to give milk, they must give birth to a child. There is no use for the young animals, which is why they are ripped from their mother shortly after birth and killed afterwards. The mother cows are then artificially inseminated again. The picture shows calves in hutches at the “Chueweid” animal farm in Drälikon Hünenberg. Approximately 300 cows and 200 calves are living on the farm.

What does that imply for the well-being of the mother and her calf? In fact, cows are very social animals which usually build strong bonds with their offsprings, making the early seperation between mother and calf particularly cruel.5 There are not only direct behavioral reactions to separation that can be observed, such as “calling” one another, but also physiological and psychological disadvantages. Studies have shown that early separation of calf and mother cow leads to severe stress, depressive symptoms and deprivation disorders in juveniles.6

Pigs

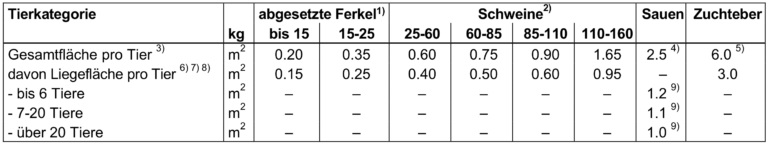

The table below shows the legal minimum requirements for piglets, pigs, sows and breeding boars.

Source: Fachinformation Tierschutz, Mindestmasse für die Haltung von Schweinen, BLV.7

Source: Fachinformation Tierschutz, Mindestmasse für die Haltung von Schweinen, BLV.7

A pig weighing 110 kg gets 0.90m² to move. Pigs have no access to pasture and no right to enter an outside area. Exercise and daylight are not legally required.

A special feature of pig farming (which is also carried out by BTS/RAUS and organic standards) is the temporarily confining of female pigs in farrowing pens. During the breeding and suckling period (before, during and after the birth of the piglets), the pig is taken to a special facility where she is held separate from the group. The law prescribes that the pen’s size must measure at least 5.5m², of which 2.25m² consists of the resting area. Although the pig must be able to rotate, she has no legal right to be led to an outside area, let alone to a pasture. In addition, she receives little to almost no entertainment possibilities and must remain alone in the bay during her whole pregnancy.8 Just as with dairy cows, pigs have their babies taken away from them shortly after birth in order to fatten them up and kill them afterwards. Until their execution, many of the mother sows spend years living indoors in confinement.

Before 1997 it was common practice to keep pigs in so-called gestation crates (this practice is still legal and widespread in many countries outside of Switzerland but is internationally considered as extremely cruel). Just as in farrowing pens, the pigs separated in crates during pregnancy and while suckling (and in some countrys during their whole life) with the difference that pigs are fixed in crates – unable to rotate or move. Permanent crate confinement was banned in Switzerland in 2007. However, the Animal Welfare Act specifies exceptional criteria for the temporary restraint of pigs in crates, which may not exceed ten days (Art. 48 para. 4 TSchV). The pigs can be kept individually in a crate during pregnancy and suckling. The pig is fixed so that they can not rotate around their own axis. The legal text reads as follows9:

During the gestation phase, the sow may be fixed in specific cases of malignancy towards piglets or limb problems (Art. 50 para. 1 TSchV). The gestation phase in which the sow may be fixed in individual cases is the period from the beginning of nest-building behaviour to the end of the third day following the birth at the longest. A record must be made of which sow was fixed and for what reason (Art. 26 para. 1 Nutz- und HaustierV).

In addition, sows are typically fixed during the (artificial) insemination process. The average number of times pig farmers make use of temporarily restraining pigs in crates is not publicly available, but research by animal rights organisations show that crates are still frequently used today.10

The mother is taken to the farrowing pen during pregnancy, where she has to wait alone for the birth of her piglets. The picture shows the whole pen. She can turn around, but there are no varied activities available to her. When her babies are born, they only stay with her for a few weeks after which they will be either prepared for fattening or used for breeding. The mother gets artificially inseminated once again.

The mother is taken to the farrowing pen during pregnancy, where she has to wait alone for the birth of her piglets. The picture shows the whole pen. She can turn around, but there are no varied activities available to her. When her babies are born, they only stay with her for a few weeks after which they will be either prepared for fattening or used for breeding. The mother gets artificially inseminated once again.

In Switzerland, the use of crates is only prohibited for permanent use. Many pig breeders keep mothers in crates in order to be able to artificially inseminate them. The female pigs must remain in the crate for several days. They can neither turn nor leave the crate to exercise. In other countries, breeding sows spend their whole lives in crates.

In Switzerland, the use of crates is only prohibited for permanent use. Many pig breeders keep mothers in crates in order to be able to artificially inseminate them. The female pigs must remain in the crate for several days. They can neither turn nor leave the crate to exercise. In other countries, breeding sows spend their whole lives in crates.

Broiler Chicken and Laying Hens

The requirements chicken farming vary according to breeding or use of the chicken. Different rules apply to the farming of laying hens (hens used for egg production) and broilers (chickens used for meat production).

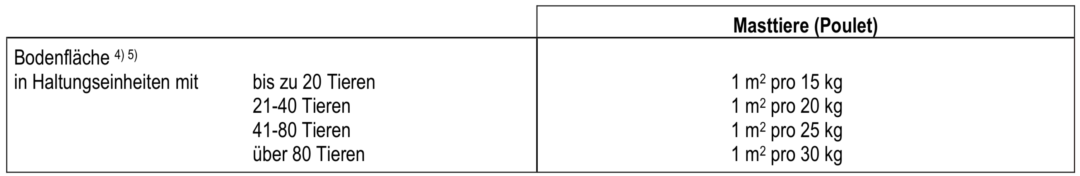

Broiler Chicken

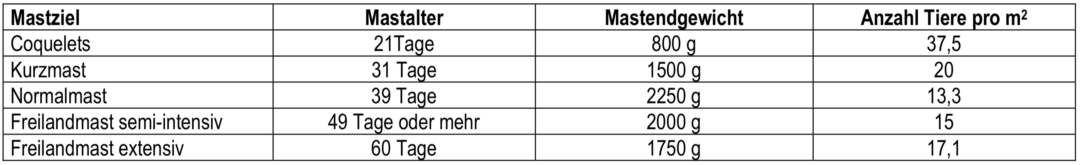

The floor area is defined as the entire accessible area available to the hens, i.e. if the animals get raised benches in the farm, the size is included in the floor area. The space calculation for chickens is not given in m² per animal, but in m² per kilogram. The reason behind is that there are different forms of poultry farming in which the chickens reach a different final weight and therefore need more space depending on the type of poultry. In short-feeding, for example, a chicken is ready for slaughter at the age of 31 days and has a final weight of 1.5 kg. Therefore, 20 chickens are found on one m². During standard-feeding, the animals are slaughtered at around 39 days old and have a final weight of 2.25 kg. Here, 13.3 chickens stay on one m² which equals the space of one A4 sheet per chicken. Broilers have no legal obligation to be offered elevated accommodation even though they are important for chickens because they prefer higher ground to feel safe and comfortable.11

Short-fattening or feeding is made possible because farmers breed special chicken breeds that display rapid growth within a short period of time. The chickens – in fact still children – already weight the same as their not overbred adult counterparts. The massive gain in weight causes broiler chickens to suffer from various health problems. To give a few examples:

-

Metabolic disorders: The main focus in broiler chicken breeding is to get the chicken to increase growth as fast as possible as well as reduce use of food. As these bred traits do not correspond with the natural needs or behaviour of chickens, imbalances arise between protein and fat deposition on the one hand and energy supply for maintenance on the other. This results in an insufficient oxygen supply and broilers consequently suffer from metabolic diseases such as heart insufficiency or oedema in lungs and heart.12

-

*Disorders due to rapid skeletal growth: Since the skeleton of broilers cannot grow normally and is overloaded, bone-related diseases commonly occur. Medical consequences include arthrosis, lameness and a loss of reproductive performance.13 Since specifically the sternum is bred as large as possible, the broiler chickens are in imbalance and often fall down or if fallen down can no longer get up on their own.

The picture shows a BTS-certified poultry farm from the company Bell in Bern. The maximum stock of chickens for meat production in Switzerland consists of 24,000 broiler chickens from the 29th to the 35th fattening day.14

The picture shows a BTS-certified poultry farm from the company Bell in Bern. The maximum stock of chickens for meat production in Switzerland consists of 24,000 broiler chickens from the 29th to the 35th fattening day.14

Laying Hens

Other than broiler chickens, laying hens are not bred with the intention of gaining as much weight as possible, but to lay as many eggs as possible. The Bankiva chicken, the ancestor of modern and industrially farmed hens, lays only 20 eggs a year, whereas our laying hens have been genetically modified to lay an egg almost every day. The heavy strain placed on the chicken’s laying apparatus leads to health problems: Inflammations of the fallopian tubes (salpingitis), peritonitis or tumours are an almost inevitable consequence of overbreeding of laying hens in the egg industry. As with broilers, many laying hens suffer from osteoporosis (due to lack of exercise) and metabolic diseases (heart disease).15 Additionally it is legally permitted and practically unavoidable to gass and kill male chicks with carbon dioxide immediately after they hatch. Since they cannot lay eggs and do not gain weight as quickly as special bred poultry they are worthless to the industry. In Switzerland, every year over 3.5 million chicks are killed on their first day of life.16

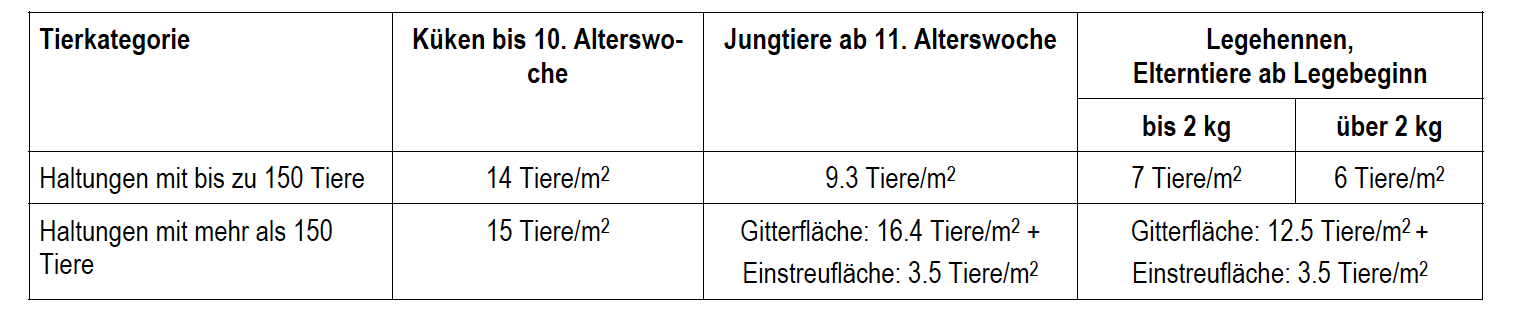

As with broiler chicken, the size is calculated on the basis of the chicken’s weight. The legally required space for laying hens is calculated according to the density of the population. If there are less than 250 chicks, 14 chicks can be kept on one square meter; if there are more than 250 chicks, 15. Seven laying hens weighing less than 2 kilograms or six weighing more are allowed per square meter. In contrast to broilers, it is a legal requirement that laying hens be provided with perches at two different heights.17

Animal Welfare has Little to do with the Well-Being of Animals

Most animals whose body parts are sold in supermarkets were kept in conventional farming systems during their lifetimes. They are kept in confined spaces, do not receive any possibility for activity, adequate bedding areas or are able to feel the sun once in their short lives. Switzerland has repeatedly praised its progressive animal welfare law, which is intended to give animals more space and dignity than their neighbouring countries. The truth is, Swiss farm animals suffer as well. The differences to other countries regarding available space differ minimally, considering that the legal limit for freedom of movement for a 110 kg weighing pig is 0.9m². Animal welfare cannot be equated with animal well-being. Anyone who is sincerely interested in animal welfare decides to completely reject the use of animals for human purposes. The Animalist does not support the view that it is permissible to exploit non-human animals if they are living under good or improved conditions, and we do not demand an improvement in living standards, but recognition of the fundamental moral rights of animals. Nevertheless, we think it is necessary to educate about the current “animal farming methods” in order to illustrate how animals must live in Switzerland.

Footnotes

-

Bundesamt für Statistik (BFS), 07 Land- und Forstwirtschaft, Neuchâtel 2019, https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfsstatic/dam/assets/7106366/master ↩

-

Daester, Daniel, Maissen, Flurin, Schweizer Mastrinder sehen oft weder Gras noch Sonne, 19.11.2013, https://www.srf.ch/sendungen/kassensturz-espresso/themen/umwelt-und-verkehr/schweizer-mastrinder-sehen-oft-weder-gras-noch-sonne-2 ↩

-

Art. 39 Abs. 2 TSchV. ↩

-

Fachinformation Tierschutz, Mindestabmessungen für die Haltung von Rindern, Bundesamt für Lebensmittelsicherheit und Veterinärwesen BLV, https://www.blv.admin.ch/dam/blv/de/dokumente/tiere/nutztierhaltung/rinder/fachinformationen-rind/1_5_rinder-mindestabmessungen.pdf.download.pdf/1_5_d_Rinder_Mindestabmessungen.pdf ↩

-

siehe zum Beispiel: Johnsena, Julie Føske et. al., The effect of nursing on the cow–calf bond, in: Applied Animal Behaviour Science, Bd. 163, 2015, S. 50–57. ↩

-

Flower, F., Weary, D., The Effects of Early Seperation on the Dairy Cow and Calf, in: Animal Welfare, Bd. 12, 2003, S 339-348. ↩

-

Fachinformation Tierschutz, Mindestmasse für die Haltung von Schweinen, Bundesamt für Lebensmittelsicherheit und Veterinärwesen BLV, https://www.blv.admin.ch/dam/blv/de/dokumente/tiere/nutztierhaltung/schweine/fachinformationen-schwein/fi-schwein-mindestmasse.pdf.download.pdf/1_(2)_d_FI_Schwein_Mindestmasse.pdf ↩

-

Fachinformation Tierschutz, Mindestmasse für die Haltung von Schweinen, Bundesamt für Lebensmittelsicherheit und Veterinärwesen BLV, https://www.blv.admin.ch/dam/blv/de/dokumente/tiere/nutztierhaltung/schweine/fachinformationen-schwein/fi-schwein-mindestmasse.pdf.download.pdf/1_(2)_d_FI_Schwein_Mindestmasse.pdf)) ↩

-

Tierschutzverordnung https://www.admin.ch/opc/de/classified-compilation/20080796/index.html ↩

-

Sennhauser, Tobias, Kein Kastenstandverbot in der Schweiz, 12.02.2014, https://www.tier-im-fokus.ch/video/kastenstand_schweiz ↩

-

Aviforum, https://www.aviforum.ch/Portaldata/1/Resources/Wissen/Haltung/DE/Normen_B7-I_d_130221_print.pdf, Technische Weisungen über den baulichen und qualitativen Tierschutz, Mastgeflügel, Bundesamt für Lebensmittelsicherheit und Veterinärwesen BLV, https://www.blv.admin.ch/dam/blv/de/dokumente/tiere/nutztierhaltung/huehner/tierschutz-kontrollhandbuch-mastgefluegel.pdf.download.pdf/Tierschutz-Kontrollhandbuch%20Mastgefl%C3%BCgel.pdf ↩

-

Scheele, C.W., Pathological Changes in Metabolism of Poultry Related to Increasing Production Levels, in: Veterinary Quarterly, Bd. 19, Nr. 3, 1997, S. 127-130. ↩

-

Thorp, B.H., Skeletal Disorders in the Fowl: A Review, in: Avian Pathology, Bd. 23, Nr. 2, 1994, S. 203-236.)) ↩

-

Art. 2 Höchstbestände, https://www.admin.ch/opc/de/classified-compilation/20130227/index.html ↩

-

Albert-Schweitzer-Stiftung, Legehennen, https://albert-schweitzer-stiftung.de/massentierhaltung/legehennen/2 ↩

-

Hofmann, Markus, Das kurze Leben der Legehenne, 23.03.2013, https://www.nzz.ch/schweiz/das-kurze-leben-der-legehenne-1.18051922, Ab 2024 nur noch weibliche Küken, in: Schweizer Bauer, 28.04.2022, https://www.schweizerbauer.ch/tiere/geflugel/ab-2024-nur-weibliche-kueken/ ↩

-

Tierschutz-Kontrollhandbuch Legehennen, Junghennen- und Elterntiere, Bundesamt für Lebensmittelsicherheit und Veterinärwesen BLV, https://www.afapi-fipo.ch/fileadmin/mr_afapi_fipo/user_upload/Documents/Prestations/PA_2018/DE/4Kontrollhandbuch-Legehennen.pdf ↩