Animal Exploitation and Fashion: The Fur Trade

Content

- How do fur bearing animals live before they are killed for fashion?

- Fur farms: A lifetime spent in captivity

- Leg-holding traps

- Animals are not clothing: How wearing animal remains denies them inherent value and merely classifies them as objects.

- How can I help fighting against the exploitation of animals for their fur?

The fur trade is booming and the industry is still experiencing constant profits. Many consumers are unaware of the positive economic situation the fur trade is currently experiencing and believe that real fur is hardly manufactured anymore. Unfortunately, this is a misconception that withstands because wearing fur is still mainly associated as a privilege of high society. Whereas the selling or exhibiting of entire fur coats declined, the industry’s production target shifted to a subtler fashion trend: real fur trims on jackets and hats. Not only does this shift lead to the wrong perception that the production of fur is no longer profitable and practiced, it also leads to ignorance on how fur is made and how non-human animals have to suffer for it.

The following article covers three topics. First, I explain the different ways of fur production and killing methods. Second, I give a short introduction to why wearing animal remains is ethically wrong and harmful in practice. Third, I offer a few suggestions on how to advocate for fur-bearing animals and how to distinguish between real fur and faux-fur.

How do fur bearing animals live before they are killed for fashion?

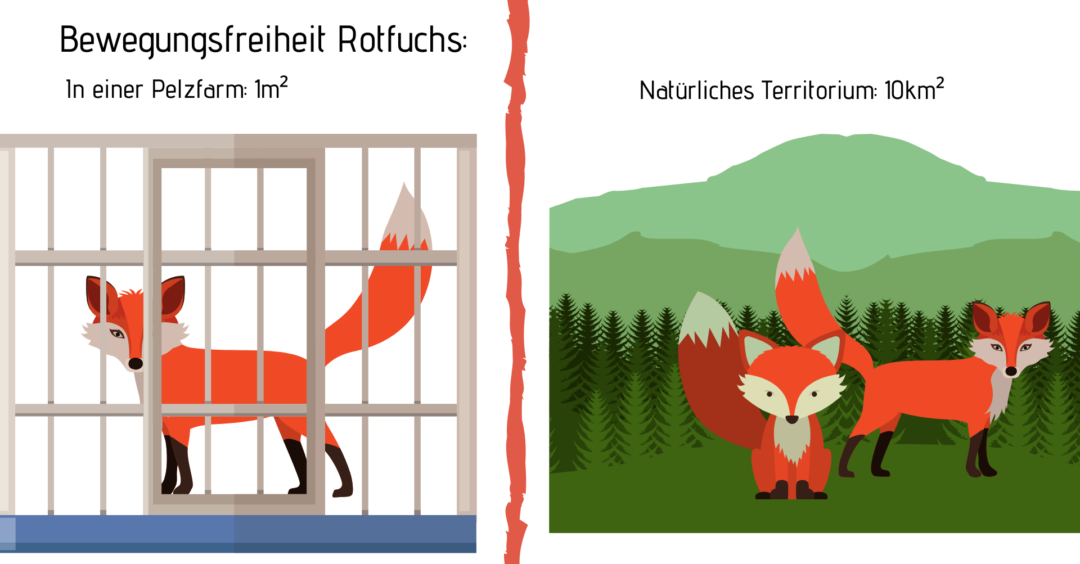

here are different methods used to exploit animals for their fur and almost all of them are prohibited in Switzerland. In Switzerland, the requirements for wildlife management are far too high as the raising and killing of non-human animals for their fur would generate any economic profits. A red fox kept in captivity must have at least a 100m² large outdoor enclosure at their disposal, whereas in a fur farm they are imprisoned in a small cage.1 Although the production of nearly every fur trim that can be bought in shops is legally considered as cruelty to animals under Swiss law, the state still allows the import and sale of fur trims produced under terrible conditions for the animals and even profits from them. In 2017, Switzerland imported 463 tons of fur and recorded a new sales high.2

Fur farms: A lifetime spent in captivity

According to the International Fur Trade Federation, approximately 85% of all fur trims originate from fur farms.3 In a fur farm, one or more different animal species are bred and kept in tiny wire mesh cages with the purpose of using their fur for human purposes. 50% of global fur production takes place in Europe, where more than 5,000 industrial fur farms are spread across 22 different countries.4 The living conditions in which the animals find themselves are miserable and – in contrast to animal agriculture – there are no standardised and compulsory regulations formulated by the European Union regarding cage farming. In addition, in many Asian countries there are no laws at all that protect the animals.5

The most common species of animals exploited for fur production are foxes, minks, raccoons, sables, martens, rabbits, dogs, cats, etc.

Foxes

Foxes kept on fur farms usually live in a wire mesh cage of less than one square meter. A covert report by an animal welfare organisation in Finland revealed that Finnish arctic foxes are fattened up to five times their normal body weight to gain a larger area of fur. The animals can hardly move anymore and suffer from bruises and inflammations on various parts of their bodies.6

Finland is the largest producer and exporter of fox fur. In 2002, more than 2.1 million foxes have been killed by the Finnish fur industry, resulting in a total profit of 250 million euros.7 Finland manages to keep fox fur sales steady and in 2016, 2.4 milion foxes were slaughtered.8

Minks

Minks are the most widely exploited animals for their fur. The fur of minks is said to account for about 85% of all traded fur – most farms are located in Europe.9 Denmark is the world’s largest producer of mink skins and is estimated to have killed about 12 million minks in 2002, generating a profit of over 514 million euros for the Danish fur industry. The production of mink fur has now even increased and according to the Danish Agriculture Council, 19 million minks are killed annually resulting in profits of 1.1 billion euros.10 The remains of the minks are not only used for clothing, but also for false eyelashes. These eyelashes are often marked as “Silk Lashes” or “Mink Lashes“. Although the fur industry states that the individual hairs of minks are obtained by regular grooming, it can be assumed that due to the additional effort and the risk of being bitten, the minks’ hair are only collected when the animal is slaughtered.11 Minks, if given a choice, spend 60% of their time in aquatic environments. They are solitary animals and highly territorial. In the fur industry, they are kept in tiny cages with dozens of other minks. The confinement and compulsive confrontation leads to self-mutilation, aggressive behaviour and cannibalism.12

All animals, including other wild animals not discussed here in detail, as well as animals killed for their flesh and those who are locked up in laboratories and zoos, suffer physical as well as psychological harm if they are severely restricted, isolated, bored and cannot behave as they would in their natural environment. Animals kept in fur farms show pathological behaviours, which indicate significant welfare problems. This includes self-mutilation, infanticide, helplessness and repetitive behavioural patterns such as monotonous pacing and the continual expression of vocals.13 Fur famers and pro-fur organisations however, are not only unwilling to acknowledge these problems, they actively try to deny them. FIFUR, the Finnish Fur Breeders’ Association, even states that keeping wild animals in cages does not affect their welfare in a negative manner. On their website the association notes:

“Even though the wild animals move around a lot, their movement is always based on a specific reason, such as finding nutrition or a mating partner. At farms, these needs are met within the cage.” – Finnish Fur Breeders’ Association14

Not only is this hypothesis by FIFUR unscientific as it disregards numerous empirical studies that necessarily link the presence of all the pathological problems listed above to lack of movement and deprivation, they also claim that movement cannot be a stand-alone need for animals, rather it is always linked to the fulfilment of a distinct goal. This is of course wrong, since non-human animals, just like humans, need movement to stay healthy and to satisfy the urge to exercise and be active. If animals no longer had the need to be active when food is provided, we would not need to lock them up in cages, nor would our dogs and cats living with us require daily outdoor exercise. FIFUR and other advocates of real fur deliberately spread false information to hide the cruel reality behind real fur production.

Killing: The animals live between 6 to 8 months and then suffer an agonizing death, since manufacturers need to adapt a technique that does not damage the animal’s fur. In Europe, minks are usually gassed with CO2 whereby they suffer from panic and feelings of suffocation. Foxes and other larger animals mostly get anally or vaginally electrocuted.14 In some countries, there are no regulations on the stunning and killing of fur-bearing animals. In China, animals get slaughtered near wholesale markets. To get there, they are often transported under terrible conditions and without any access to food and water. When the animals arrive at their final destination, they are dragged out of their cages by the neck with a pole to which a wire noose is attached. Two methods of stunning or killing are common. Sometimes the animals are strangled either with the noose or a worker stands on their neck and exerts constant pressure on them until they suffocate. However, since this method is time-consuming, the animals are often beaten to death or to unconsciousness. In this case, the worker holds the animal by their hind legs and crushes their skull with a heavy object or smashes the animal’s head against a wall or onto the floor. When the animal is no longer able to defend themselves, they get skinned. Although many non-humans display difficulties to move because of the hits, they are still conscious when their fur is removed. Video documentation, research papers and field reports show how animals struggle and scream during skinning and continue to breathe for five to ten minutes after their fur is completely removed.15

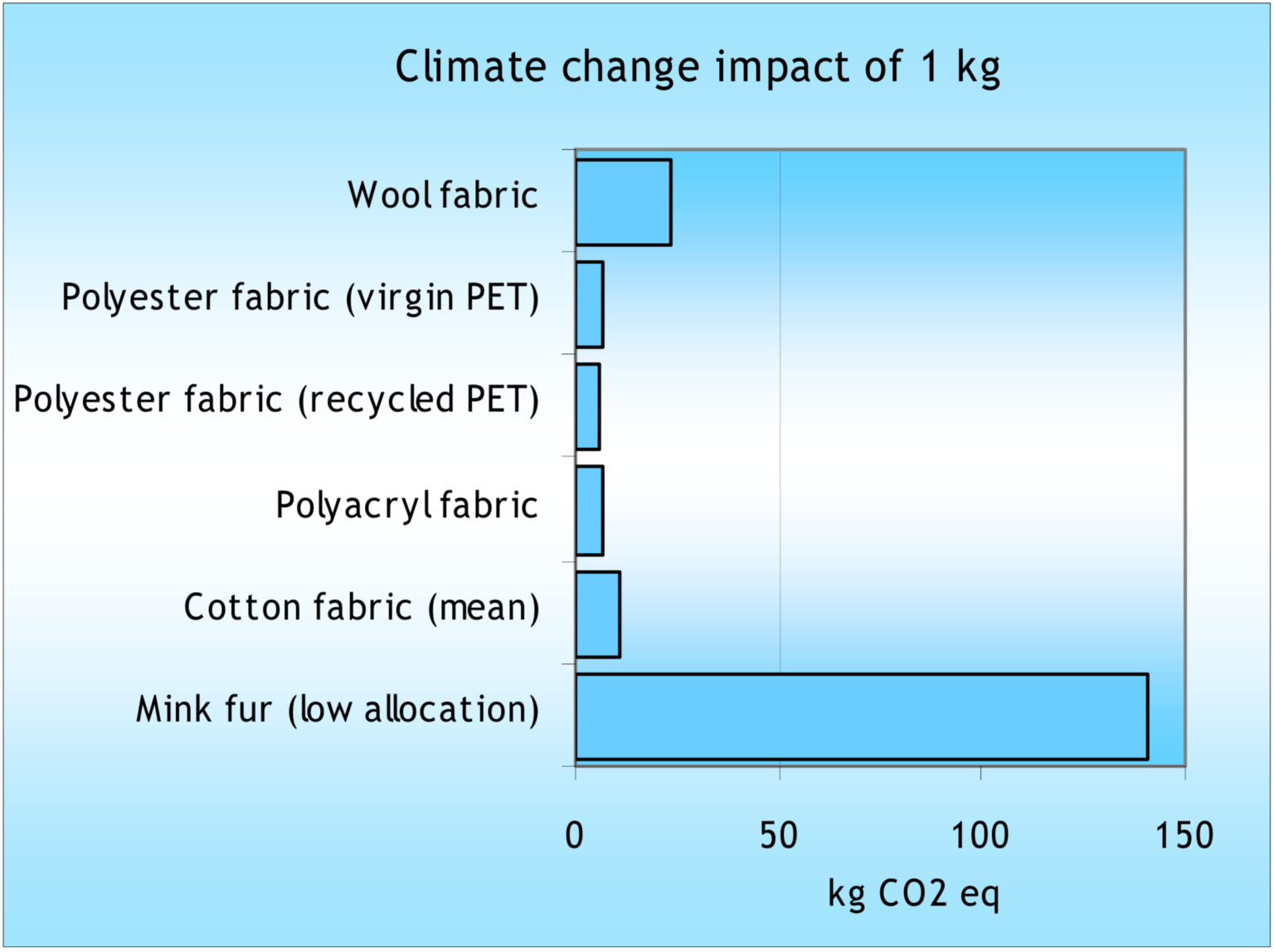

Are furs sourced from fur farms sustainable? No. It is a common misconception that real fur is sustainable. The farming of fur-bearing animals is damaging to the environment. On the one hand, the animals have to eat food and drink water during the 6 to 8 months of their lives and therefore need a lot of resources and secondly, their excrements lead to increased N2O emissions.16 Various studies have evaluated the overall environmental impact of the processing of fur, faux fur, wool and cotton and concluded that real fur not only creates the largest ecological footprint, but its production requires 20 times more energy than faux fur made out of polyester.17

In addition, fur is literally the skin of an animal and this skin will start to decompose if it is not made durable. In order to prevent decay, fur is treated with various chemicals. The most commonly used chemicals are formaldehyde, which can cause or support the outbreak of leukemia, and chromium, which has been proven to be carcinogenic. Tests carried out by the Bremen Environmental Institute on the fur trimmings of children’s jackets from Canada Goose, Versano, Nickelson, etc. revealed that the levels of both chemicals were far above the maximum levels approved by the EU or the Oeko-Tex Standard 100.18 Fur is therefore not a "natural product", but extremely processed. At last, transport emissions must also be added to the environmental impact, as the chemical treatment of animal remains often takes place at a different location from the fur farm or even in another country. The furs are then usually distributed by plane.

Leg-holding traps

The other 15% of furs are taken from wild animals who are either caught by traps or shot by hunters. In countries like the US and Canada it is still allowed to trap animals with iron-traps and it is mainly coyotes, wolves, bobcats, raccoons and otters that fall victim to the practice. Contrary to the common belief that coyotes are killed due to population control, the main reason for trapping in Canada is the fur trade. In 2009, 730’915 wild animal furs were sold and 70’000 Canadians work in the fur industry.19 Most traps are set up in such a way that when the animal steps on them, the trap is triggered and his leg gets stuck. Trapped animals panic and try to free themselves. Sometimes they attempt to bite through their own leg to escape. Many animals die trying. Other common causes of premature death due to the trapping are dehydration, hypothermia or blood loss.20 Since a lot of mothers get caught in the traps, their young also die as she cannot return home to them.

When the trappers show up to pick up their victim, the animals, if they have not already died in some other way, are either shot or – in order to not damaging the fur – strangled by standing on the animal’s neck for several minutes and keeping constant pressure on it.21

Is fur taken from animals caught by traps sustainable? Even though certain fur selling companies like describe the selling of fur by iron traps as environmentally friendly and sustainable, it in fact is not. First, it is impossible to control which kind of animals are caught in the traps. While Canada Goose claims that only non-endangered animals are killed, neither the company nor the trappers have control over it and dead animals belonging to endangered species are repeatedly found dead as a result of being stuck in the trap.20 The American Veterinary Medical Association states that 67% of all animals captured in traps (including dogs and cats) cannot be used for fur production. As it is illegal to kill endangered species, it can be assumed that a lot of incidents do not get reported and that there is an estimated number of unknown cases about the current extent of endangered animals killed by traps.22 In addition, furs sourced from wild animals – just like those from fur farms – are treated with toxic chemicals and shipped internationally.

Animals are not clothing: How wearing animal remains denies them inherent value and merely classifies them as objects.

There are several reasons why fur shouldn’t be worn and why it is not a matter of free choice.

a.) Everyone has a right to freedom only insofar as they don’t endanger the freedom of others in a significant way.

As has already been discussed, the production of fur is associated with immense animal suffering, which never can be compensated by the benefits we derive from wearing their skin. Real fur is a fashion accessory – not a necessity to stay warm in the cold season. If we accept the mistreatment of these animals just to satisfy our vanity, the decision isn’t based on rational considerations or compassion, but on pure egoism.

In his famous book “On Liberty” (1859), the philosopher John Stuart Mill examines principles relating to the freedom of an individual to do what he or she wants and to draw a line where this freedom ends. To do that, he introduces the “harm principle”.

The Harm Principle The harm principle states that the freedom of an individual may be interfered with if and only if the action to be refrained from causes relevant damage to other sentient beings. In other words: Your freedom ends where the freedom of another is harmed in a significant way.

The harm principle is a relatively uncontroversial principle since its truth is almost undeniable. Let us imagine that an entrepreneur wants to integrate a product into the market, whose production results in an enormous health burden for humans and non-humans. The entrepreneur is now forced to abandon his project because of laws that regulate the protection of the public from toxic pollution. Although the entrepreneur could claim that this decision is unfair because it interferes with his freedom of action, his reasoning seems unsatisfactory as we share the intuition that his claim to build the company and generate profits is less convincing and valuable than the health risks of all the living beings affected by his decision.23

It is now questionable why this principle should not be extended to non-human animals. Animals are sentient, intentional and intelligent beings who display a desire to live and display aversion when they are hurt, harmed or exploited. Every person who supports the fur trade doesn’t respect the animals’ freedom and puts their harm above trivial needs. Every animal that gets killed to serve human desires or pleasures – no matter what life he had before – has his freedom to exist taken from him and this is irrational and morally unacceptable.

b.) Should we be wearing fake furs or furs that we have already purchased?

The reason why we shouldn’t wear fur, then, is because non-human animals have certain basic rights – as the right to live – or moral status that we don’t respect when we consider their skin as fashion objects. The following statements and behaviours are therefore problematic:

"I am not going to buy new fur trims, but I’ll still wear the one I already bought, so that the animal hasn’t died unnecessarily / […] to honour the animal." Anyone who makes a statement as such suggests that real fur should be continued to be worn to pay homage to the killed animal. The intention behind this attitude may be a good one, but it is actually very harmful to the greater cause and, in addition, speciesist. The practical disadvantage consists in the fact that every piece of fur that is worn in the public advertises dead animal parts as fashion. If you refuse to buy new fur trims in the future but continue to wear your Canada Goose jacket with fur collar in public, you may encourage other people to buy a jacket containg fur as well, because they consider the overall jacket or specifically the fur part fashionable or aesthetical. Especially younger individuals or people who aren’t well informed about the fur trade feel encouraged to buy real fur if they see others wearing fur. If you care about the honour or dignity of the animal who died because they were born with fur, then destroy the fur trim. The lives of her relatives might depend on it.

Furthermore, ideas such as “paying final tribute to the animal” or “appreciating them post mortem” are purely human-made and metaphysical concepts and it is questionable to what extent they really honour or benefit the dead animal, even if it wouldn’t have the above-mentioned disadvantages for other fur-bearing animals. This statement seems to be subject to a speciesist thought that classifies animals as objects and values the act of “recycling” their body parts more than dismantling speciesist practices. For example, would we wear a necklace made of real human teeth without those humans former consent to pay last respects to people who have died? Would we feel beautiful and special wearing remains of people who were first tortured and then brutally murdered in a prison camp? Would we also state in this case that we use certain body parts of them so that they did not die for nothing but were still useful in some way?

The reason why we do not express the same rejection of the utilization of animal remains is based on the speciesist attitude that non-human animals have no inherent value and exist only for our benefit. Even if someone is now actively speaking out against the new production of fur, but at the same time is still wearing it, the animal is not yet perceived as a valuable and independent individual, but as a product. The very concept of non-human exploitation – the complete commodification of non-human life – is a consequence of the fact that we do not attribute moral status to them. Wearing body parts of any kind of animal – be it fur, the skin of cows or lambs, or the wool of sheep – is always connected with the subliminal message that animals are objects, items and clothing.

"I only buy fake fur" Many of the problems discussed in the previous section also apply when people decide to wear faux fur. It is clear that on ethical grounds it is always preferable to buy fake fur rather than real fur. Nevertheless, it is possible that fake fur gets confused with real fur and may give others the impression that wearing fur is generally accepted and justified. In addition, we are faced with the question of whether the imitation of dead animal remains does not further promote commercialization and the commodification of animals. To avoid taking this unnecessary risk, we reject all fabrics and textiles associated with non-human animal skin or body parts – and because the production of fake fur is not sustainable as well.

It is only when we abandon the idea that non-human animals are commodities and realize that their body parts are solely aesthetic on them, that we move in the right direction to fight against speciesism and regard animals for what they really are: individuals, agents and inherently valuable living beings.

Conclusion: Nur dann, wenn wir die Idee aufgeben, dass nicht-menschliche Tiere Waren sind und erkennen, dass ihre Körperteile nur an ihnen selbst ästhetisch sind, begeben wir uns auf den richtigen Weg, den Speziesismus zu bekämpfen und Tiere als das anzusehen, was sie wirklich sind: Individuen, Akteure und inhärent wertvolle Lebewesen.

How can I help fighting against the exploitation of animals for their fur?

There are several actions which can be carried out to help fur-bearing animals.

- Do not buy real fur: If you still want fake fur trimmings, make sure they are fake. Although there is an obligation to declare real fur in Switzerland, this obligation is insufficiently fulfilled and it even happens that furs are declared as fake, although they are real. You can recognize real fur by certain characteristics: The hairs of real fur move individually when the person moves or the wind blows. They are thin, finer and have different hair lengths. Fake furs only have one layer of hair and the stitching or the net to which the fur is attached to is visible when you pull the hairs apart. Real fur has different layers of hair and you can recognize the undercoat and the skin of the animal instead of the stitching. If you can touch the fur, you can also attend the fire test; rip out two or three hairs from the trim and set them on fire. If they smell like burnt hair, the fur is real. If they smell like plastic, it’s fake.24

- Fur-Shaming: Fur-shaming, the public exposure of people wearing fur, is a common form of anti-fur activism. Ask local organizations if they can send you stickers and attach them to fur collars (If you live in Switzerland, contact furfoe.ch). Fur-shaming is a way to make the wearing of fur socially unacceptable and it appeals especially to those who have no interest in animal well-being and can only be convinced by shaming them.

- Try to talk to people who wear fur: If you have no reservations confronting them, you can try to inform them about the production of fur or about the ethical principles that oppose fur wearing.

- Distribute leaflets: Distribute leaflets containing information about fur. You can download and use our flyer for free or you can ask local anti-fur or animal rights organizations if they provide existing flyers.

- Contact companies: Write emails and letters to fur selling companies (Escada, Bogner, Moncler, Dolce & Gabbana, Fashion Stylers, etc.) and demand that this cruel practice be stopped and they remove real fur from their assortment. Express your anger about the sale of fur by these companies on their social networks or write reviews criticizing it.

- Demonstrations: Take part in demonstrations against the fur trade or protest outside shops that sell fur.

- Learn about animal rights and extend your opposition to animal exploitation to other species: If you want to stand up against fur, you already believe that animals should not be tortured or exploited. Unfortunately, fur-bearing animals are not the only ones that are exploited for specific characteristics. You can find out about other forms of animal oppression and try to adopt a vegan lifestyle.

- Tierschutzverordnung (TschV), Anhang 2, Tabelle 1, Gehege für Säugetiere, https://www.admin.ch/opc/de/classified-compilation/20080796/index.html↩

- Voegelin, Julia, Pelz-Boom in der Schweiz. «Wer Pelz trägt, ist mitschuldig am Leid der Tiere», in: SRF, 18.02.2017, https://www.srf.ch/kultur/gesellschaft-religion/wer-pelz-traegt-ist-mitschuldig-am-leid-der-tiere↩

- Finger weg von echtem Pelz, in: Zürcher Tierschutz, https://www.zuerchertierschutz.ch/tierschutzthemen/pelz-und-pelztiere.html↩

- Europe Regulations, in: Sustainable Fur, 2017, https://www.wearefur.com/responsible-fur/farming/fur-farming-europe/↩

- Internation Fur Trade Federation, The Socio-Economic Impactof International Fur Farming, 2003, S. 1 https://web.archive.org/web/20110713004402/http://www.iftf.com/publctns/4849Intls_eEng.pdf, Fakten zur Pelzproduktion, in: ProTier – Stiftung für Ethik und Tierschutz, http://www.protier.ch/site/index.cfm?id_art=97250&actMenuItemID=45057&vsprache=de↩

- Kägi, Marianne, Das Leiden der Polarfüchse, Billiger Echtpelz – den Preis zahlen die Tiere, 05.12.2017, https://www.srf.ch/news/schweiz/das-leiden-der-polarfuechse-billiger-echtpelz-den-preis-zahlen-die-tiere↩

- U.S. International Trade Comission, Industry and Trade Summary. Furskins, in: Office of Industries, Washington 2004, S. 20., Internation Fur Trade Federation, The Socio-Economic Impactof International Fur Farming, 2003, S. 11, https://web.archive.org/web/20110713004402/http://www.iftf.com/publctns/4849Intls_eEng.pdf↩

- Arctic foxes, fur and Päntsdrunk – Finland in the World Press, in: Helsinki Times, 01.06.2018, https://www.helsinkitimes.fi/149-finland/15582-finland-in-the-world-press-arctic-foxes-fur-and-paentsdrunk.html↩

- Hansen, Henning Otte, European Mink Industry – Socio-Economic Impact Assessment, 19.09.2017, S.2.↩

- Mink and Fur, in: Danish Agriculture & Food Council, 2019, https://agricultureandfood.dk/danish-agriculture-and-food/mink-and-fur#, Facts, in: Kopenhagen Fur, https://www.kopenhagenfur.com/en/about-kopenhagen-fur/facts/↩

- Nerzwimpern, in: Deutscher Tierschutzbund E.V., https://www.tierschutzbund.de/aktion/mitmachen/verbrauchertipps/nerzwimpern/↩

- Mink Farming, in: CRAFT. Coalition to Abolish the Fur Trade, https://www.caft.org.uk/mink_farming.html↩

- ACTAsia, China’s fur trade and its position in the global fur industry, 2019, S. 40, Hsieh-Yi, et al., Fun Fur?, A report on the Chinese Fur Industry, 2004/2005, S. 5, http://www.davids-revenge.de/download/Furreport05pdf.pdf↩

- aus dem Englischen übersetzt, FIFUR, 2020, https://fifur.fi/en/q↩

- Hsieh-Yi, et al., Fun Fur?, A report on the Chinese Fur Industry, 2004/2005, S. 6, http://www.davids-revenge.de/download/Furreport05pdf.pdf, ACTAsia, China’s fur trade and its position in the global fur industry, 2019, S. 39f., Fur Farming, in: Fur Free Alliance, https://www.furfreealliance.com/fur-farming/↩

- Bijleveld, Marijn, et al., The Environmental Impact of Mink Fur Production, in: Delft, 2001, S. 7.↩

- Hoskins, Tansy, Is the fur trade sustainable?, in: The Guardian, 29.10.2013, https://www.theguardian.com/sustainable-business/sustainable-fashion-blog/is-fur-trade-sustainable↩

- Die Mär vom Naturprodukt Pelz, in: NDR, 07.11.2014, https://www.ndr.de/ratgeber/verbraucher/Naturprodukt-Pelz-mit-Schadstoffen-belastet,pelz132.html, Preusse, Simone, Pelzbesatz ist nicht nur grausam, sondern auch krebserregend, in: Fashion United, 19.01.2016, https://fashionunited.de/nachrichten/mode/pelzbesatz-ist-nicht-nur-grausam-sondern-auch-krebserregend/2016011919494↩

- Proulx, Gilbert, Fur Trapping, in: The Canadian Encyclopedia, 2015, https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/fur-trapping↩

- Protection of Fur-Bearing Animals, https://thefurbearers.com/other-faqs/what-about-canada-goose↩

- Fur Trade Facts, in: Last Chance for Animals, https://www.lcanimal.org/index.php/campaigns/fur/fur-trade-facts↩

- Literature Review on the Welfare Implications ofLeghold TrapUse in Conservation and Research, in: American Medical Veterinary Association, 2008, https://www.avma.org/resources-tools/literature-reviews/welfare-implications-leghold-trap-use-conservation-and-research↩

- Auch wenn dieses Prinzip in der Theorie von allen angenommen wird, ist es in der Praxis auch was unsere Mitmenschen anbelangt, nur unzureichend umgesetzt. Die Textilindustrie als Ganzes beispielsweise, bereichert sich an der Not und dem Leiden vieler Menschen, die in Nähfabriken zu einem Hungerslohn hart und ungeregelt viel arbeiten müssen. Auch die Fleisch- und Milchindustrie ist nicht nur schädlich gegenüber Tieren, sondern führt dazu, dass indigene Völker in Brasilien ihre Heimat verlieren, da Regenwaldrodungen Platz für die Rinderhaltung und den Sojaanbau für die Nutztierwirtschaft machen soll. Ausserdem werden Massentierhaltungsfarmen und Schlachthäuser in den USA zum Beispiel in Gebieten gebaut, in denen in erster Linie Menschen mit dunkler Hautfarbe leben. Wir müssen das Schadensprinzip öfters einbeziehen, wenn wir Produkte kaufen und wir haben die Pflicht, uns darüber zu informieren, inwiefern unsere Handlungen bzw. unsere Freiheit eine Handlung auszuführen, dazu führt, dass einem anderen Lebewesen in relevantem Masse geschadet wird.↩

- FurFoe, Pelz erkennen, https://furfoe.ch/info1↩