Arguments Against Veganism

Content

- Lions eat meat too

- A vegan diet is unnatural

- Humans have always eaten flesh

- Morality is subjective. Everyone should do what they think is best

- Animals were made to be eaten by humans

- Eating animals was essential for human evolution

- Vegans are responsible for the deforestation of the rainforest

- I only eat organic meat produced on farms where the animals could live happy lives

Lions eat meat too

People often justify the consumption of meat by claiming that predators such as lions also eat meat. The argument against veganism is as follows: Because lions and humans are both capable of killing other animals, there is nothing wrong to eat non-human animals. There are several misconceptions behind this idea.

Error number one: thinking that lions are a guide to what's ethically appropriate

The first fallacy is to assume that a lion's behaviour can tell us something about how humans should behave. If we think it's morally justified to eat flesh just because lions (or other predators) do, we must somehow assume that a lion's behaviour sets a standard for evaluating moral issues. But this is absurd. If lions were a benchmark for appropriate moral behaviour, then it would be justified for humans to kill or even eat unwanted, physically weak or unloved children (as lions sometimes do), or to fight territorial battles. Human behaviour cannot be justified by the behaviour of lions because, unlike humans, lions are not moral agents, they are moral patients. To be a moral agent means to be sufficiently rational to establish moral principles and to reflect on the rightness or wrongness of certain actions. Lions are simply unable to do so.

Error number two: thinking that humans are predators

The implicit assumption that humans, like lions, are predators is simply wrong. Although humans have succeeded in controlling nature and non-human animals, this does not automatically make humans typical predators. Unlike wolves or lions, we don't venture out into the wild every day to ambush our dinner and kill it with our bare hands (or teeth) if the opportunity arises. Most of us don't hunt or grow our own food. Instead, we rely on agricultural and industrial systems to provide us with food. Whether I buy a carrot in the shop or a piece of a dead animal - neither of these things makes me a predator.

Error number three: thinking that humans are carnivores

Lions are carnivores, humans are not. "Carnivore" is a technical term for an animal that eats meat as its primary food source. Carnivores differ anatomically from herbivores in that they have a shorter digestive tract and can digest meat more easily. The teeth of a carnivore are shaped for tearing apart prey, not for grinding plants. Lions are able to tear their prey apart with their sharp fangs and digest the raw flesh. Humans can't do that because they are not carnivores, they are omnivores. Humans can digest processed dead animals, but they can do the same with many plant foods. While the human digestive system cannot handle a lot of raw meat, it does allow for a purely herbivorous diet.

Note: Although comparing humans with other animals does not hold much promise for answering ethical questions, it would be most obvious to compare human diets with those of our closest relatives - the great apes. However, the diet of the great ape is quite different from that of the lion, as the great ape basically eats only plants.

A vegan diet is unnatural

The argument that justifies the killing and use of animals on the basis of "naturalness" as the decisive criterion for moral rights can be subject to several objections:

Some Fallacies

The Appeal to Nature Fallacy is a logical fallacy that occurs when someone claims that something is morally right or acceptable simply because it is natural, or that something is morally wrong or unacceptable because it is unnatural. The fallacy arises from the mistaken assumption that what is natural is inherently good or morally superior, while what is unnatural is inherently bad or morally inferior. However, this assumption overlooks the complexities of moral reasoning and the fact that not everything found in nature is ethically desirable.

Another fallacy is rooted in philosopher David Hume's is-ought problem, which highlights the distinction between descriptive statements about the way things are and normative statements about how things ought to be. Just because something is a certain way in nature, it does not provide a moral justification for why it should be that way. The statement: "Humans have always been competitive and aggressive throughout history, so competition and aggression are morally justified", for example, falls foul of the is-ought fallacy. In this example, the is-ought fallacy occurs when the factual claim that humans have always been competitive and aggressive throughout history is used to derive the moral claim that competition and aggression are morally justified. The fallacy lies in the assumption that just because something is a certain way (the "is" or factual claim), it automatically implies how it ought to be (the "ought" or moral claim). However, this argument overlooks the need for additional ethical considerations and fails to provide a valid justification for the moral claim being made.

Similarly, the claim that it is morally right to eat flesh simply because it is "natural" for humans to do so is invalid. The conclusion that "eating flesh is morally permissible" cannot be derived from the factual claim that humans have always eaten flesh, or that humans are capable of digesting flesh.

If naturality dictates what is morally good, then we have to refrain from many of our everyday actions

Anyone who relies solely on "naturality" as the fundamental criterion of moral rightness faces a significant dilemma. Before I will explain the dilemma, it is crucial to clarify the meaning of the term "natural". One way of defining "naturalness" is to say that something is natural if it is as close as possible to nature, or if it is a product of natural processes. Conversely, "unnatural" or "artificial" can be seen as the opposite, referring to things that are not derived from natural processes. Examples of such artificial products include pharmaceuticals, contraceptives, preservatives, make-up, steroids, artificial insemination, synthetic flavours and many more. These items are not simply found in nature, but have (for the most part) undergone artificial processing.

So, what is the dilemma that the advocate of the natuality-argument must face?

One horn of the dilemma is that the ethical implication of this statement (namely that what is natural is good and what is unnatural is bad) would also require us to abstain from other unnatural behaviours. If we are to live in harmony with natural processes, we must question the use of antibiotics, contraceptives, make-up and much more.

The second horn of the dilemma brings us back to the animal kingdom: if we were to adhere strictly to what is considered natural, the consumption of animal products would pose significant challenges. Many practices involving animals, both in industrial and even organic contexts, are inherently unnatural. Factory farming, for example, deprives animals of most natural needs and behaviors. In the dairy industry, for example, female cows are constantly artificially inseminated and their genetic makeup is manipulated to maximise milk production. While cows have a natural life expectancy of 20 to 30 years, in the dairy industry they are typically slaughtered at the age of five. Similarly, broiler chickens are slaughtered at just 31 days old, when under natural conditions they could have lived for up to 10 years. In addition, the processing and consumption of meat involves several practices that differ from natural processes. Meat is not eaten immediately after slaughter, but is stored, preserved and packaged. Similarly, milk is filtered to make it safe for human consumption. It is worth noting that cow's milk is biologically intended for calves, not (adult) humans, which further calls into question the naturalness of its consumption in our diets.

To assume naturalness as a morally relevant criterion for granting moral rights is not a satisfactory option for people eating flesh; on the contrary: the argument contradicts itself.

Humans have always eaten flesh

A popular potential counter-argument to veganism is the idea that humans have always eaten flesh, and that it is therefore morally legitimate to continue to do so. Using human history as a reference point for assessing moral issues does not make sense, since it can be observed that people have often done things or maintained traditions that were later considered inadmissible, cruel or wrong.

It is important to recognise that simply appealing to historical precedent or tradition as a justification for certain beliefs or actions is not a valid argument. To illustrate this point, let's consider two examples. A conservative might argue: "Throughout history, people have oppressed minorities, so it is perfectly acceptable for me to do the same". Similarly, a sexist person might argue, "Women have been historically oppressed by men since the dawn of civilisation, so why should we change that?" However, most of us would reject these statements because we understand that reference to human history alone cannot morally justify such beliefs because they perpetuate discrimination and harm.

By acknowledging the flaws in these examples, we recognise that the mere fact that something has been practised throughout history does not automatically make it morally acceptable or desirable. We understand that ethical judgements should be based on principles of fairness, equality and respect for the rights and welfare of all individuals, rather than on historical patterns of behaviour. History should serve as a lesson to be learned, not as a blanket endorsement of the perpetuation of harmful ideologies or actions.

*Comment on the legitimate use of examples dealing with the oppression of certain human beings: The examples do not claim that racism and sexism no longer exist, nor do they aim to devalue or suppress people who are still victims of racist, sexist or other oppressive behaviour on a daily basis. The focus concentrates on the statement that we are not able to justify the exclusion of humans or non-human animals from the sphere of morally considerable beings by referring to history or traditions. Attempts to justify concepts such as racism, sexism, ableism, ageism and speciesism through historical realities must be rejected and condemned because they are arbitrary and neither provide a plausible nor coherent argumentative basis. To fight and argue for animal rights should include to fight for all moral considerate species and argue against the unjustified und systematic oppression of humans.

We do not typically base moral rights solely on ancestral practices. Instead, we prioritize examining the reasons why we should avoid oppressing others and rely on universal values, such as justice, that determine certain actions as either commendable or objectionable. When discussing the significance of women's right to vote, we might emphasize that "women possess equal cognitive abilities to men, so there is no justification for excluding them from voting" or "individuals should not be judged based on their gender." In light of this, it is crucial to question why, in the context of animal treatment, we fail to inquire about the criteria essential for ascribing moral rights. The majority of animals are sentient beings, capable of demonstrating intelligence and creativity. They are capable of forming and maintaining social bonds with other beings, and they experience suffering when subjected to adverse circumstances.

Just because humans have always behaved in a certain way or followed certain traditions, it does not follow that these behaviours or traditions are still acceptable. Rather than denying animals rights because we have always done so, we should ask whether animals do not possess qualities or capacities such as sentience or intentional states (desires, beliefs) that make them morally significant beings.

Morality is subjective. Everyone should do what they think is best

It is true that ethical questions are not easy to resolve. For many centuries there has been no consensus about which ethical theory is the best or most coherent. But this does not mean that morality is a subjective matter. A closer look at the world of common sense reveals that ethics is not perceived as a subjective matter, but rather that most people expect their own ethical beliefs to be generally accepted.

An example from our everyday world may help: The generality of moral values becomes clear when we blame someone. Imagine a friend promises to help you move house. On the day of the move, she calls to say that she's got the flu and can't help. Now suppose you somehow find out that your friend did not have the flu, but made up an excuse to avoid the unpleasant work. Everyone - except the moral sceptic - feels entitled to criticise your friend for her behaviour. Why do we do this? Because we believe that it is always wrong to lie or break a promise without a good reason. So if we think that morality is just a matter of taste or personal preference, then there is no point in criticising other people for their behaviour - because the person who holds a particular opinion does not necessarily think that their attitude is wrong in the first place.

These observations pose a problem for someone who claims that morality is merely subjective. One possible answer to avoid these undesirable results would be to admit that morality is somehow objective - but only within a particular culture. Other countries and cultures may have different moral rules and concepts. Morality is therefore relative to certain cultures. But again, moral relativism is fraught with difficulties:

- Difficulty number one: If moral relativism is true, then all moral reformers have made a systematic mistake. People who fought against the institution of slavery, for example, would all have violated the prevailing moral code. The reformers would therefore have developed a false judgement and therefore behaved irrationally in their act of fighting against existing moral rules. It seems, however, that no one really takes this view.

- Difficulty number two: If moral relativism is true, cross-cultural evaluation is impossible. If another country with a different value system violates basic human rights, e.g. female circumcision, child labour, systemic racism, stoning, public castigation, etc., we cannot criticise it.

- Difficulty number three: If moral relativism is true, then transcultural and intracultural criticism is no longer possible. Transcultural criticism is not possible because we cannot claim that systemic racism is bad no matter where it is practised. This view doesn't make sense because we usually believe that it is useful to evaluate and criticise the moral codes of different cultures. Intercultural criticism is no longer possible because we cannot claim that our society today is morally superior to the past simply because people in the past had different ideas about right and wrong (i.e. we cannot criticise the fact that homosexuality used to be despised and punished in our country or culture). But this does not make sense either, because we think that the moral code in one's own society can change for the better or for the worse, and we feel entitled to condemn crimes against people (or animals) that our society has committed in the past.

While ethics may not be an area where a single correct view can be identified as clearly as in mathematics, it does not follow that there cannot be a strong or decisive tendency towards certain poles that are considered right or wrong and which are then recognized as objective. Since vegans focus on the suffering of animals and think that it is fundamentally wrong to be allowed to treat sentient creatures as properties, vegans make an objective claim to these convictions and won’t accept it from a moral perspective if others still continue to eat meat or consume dairy.

Animals were made to be eaten by humans

To assume that the sole purpose of animals' existence is to be eaten or used by humans is to assume that there is something in the world that determines (or has determined) meaning, purpose, or destiny. If someone tries to use this approach to argue against veganism, they must first provide information about the metaphysical beliefs they are assuming. For example, even if you want to attribute this assumption to the existence of God, his construction of the world and the hierarchies within it, there is convincing scientific data and theory to the contrary.

The most important theory that contradicts the foregoing statement is evolutionary theory. Charles Darwin, the author of the theory of evolution, as well as many other contemporary evolutionary biologists, consider the thesis of continuity between non-human animals and humans to be true. Roughly speaking, evolutionary theory is based on the idea that all living beings are descended from common ancestors who then – over millions of years – developed differently or differentiated into different species. Evolutionary theory is a widely accepted foundation in science because it can plausibly explain why animals, especially mammals, have an almost analogous anatomical structure compared to humans.1 The thesis that the existence of the human species can be traced back to a common ancestry shared by many animals thus contradicts the religious belief that man is the “pride of creation” since, according to the implication of Darwin’s theory, the emergence of man did not happen by miracle, but by the continuous evolution of species. At the same time, this also means that many species already existed when humans, as they exist now, had not yet evolved. Homo sapiens is a fairly recent species - and this makes the plausibility of the counter-argument even less likely, since it simply cannot be that animals were "made" for us humans.

Eating animals was essential for human evolution

The scientific community actively debates the origins of human rationality, consciousness, and linguistic capabilities. Researchers propose that the key to these extraordinary human abilities lies in our brains, which exhibit a larger size relative to the human body. This prompts us to question the factors that contributed to the evolution of Hominini, a tribe of great apes, into the genus Homo, encompassing our own species and the now-extinct Neanderthals.

One popular approach to explaining this question correlates brain growth with meat consumption. The ancestors of Hominins initially lived in the wet forests of Africa. Over the last three to four million years, they migrated to grasslands, leading to a number of behavioural and dietary adaptations. Digestible plant foods were harder to come by in the new, drier environment than in the wet forests, but the grasslands were home to a large number of grazing animals. This led Hominins to change their diet, at least in part.2

Carel van Schaik, an anthropologist working at the University of Zurich, sums up the hypothesis as follows: “Man has become so incredibly clever because of his diet and his ability to obtain food”.3

What does this mean? In summary, the hypothesis is that a large brain requires more energy and that this energy could only be provided by ingesting energy-rich meat (since fruit is not a good energy source). It is thought that Hominins, after relocating to less humid areas, first consumed carcass remains and then, over time, switched to hunting. The increased consumption of meat led to an increase in energy supply, which in turn led to physiological and metabolic adaptations4 (e.g. cranio-dental changes, as less emphasis was placed on grinding and more on biting and tearing animal meat, such as the reduction of the gastrointestinal tract) and to an enhanced ability to act intelligently.2

Before discussing in more detail whether this theory, if true, has ethical implications for our current way of life, I will show that the thesis - as much as it is quoted in the media - is not considered plausible by everyone in the scientific community.

A group of researchers led by Karen Hardy and Jennie Brand-Miller have recently published a scientific paper that aims to show that the consumption of meat was important, but not sufficient, for the evolution of Homo sapiens. The researchers argue that the emerging ability to cook food and the associated frequent intake of starch - a storage carbohydrate found only in plants - was of considerable importance throughout the evolution of Homo sapiens. Their main thesis is that high-energy starches (cooked starches) were essential to meet the increased metabolic needs of the enlarged brain; starch only becomes high-energy when cooked, and digestion of this type of starch facilitated the increase in brain size (they also believe that this approach can explain the reduction in gut size as fibrous plants were gradually replaced by more energy-efficient plant foods).

The researchers assume that vegetable foods with a high starch level constituted a rich, reliable and important part of the diet and offered a number of survival advantages over meat consumption:

- The energy required for gathering plants may have been much lower than that required for hunting.

- Plant-based energy sources were more reliable than meat, as they were more common and could later also be used as a winter resource in northern areas.

- Consumption of high-energy starch enabled increased aerobic capacity and promoted reproduction; in other words, starch was likely to be an energy source of considerable value for hunting, which was accompanied by extensive physical performance.5 Hardy believes that if Hominins had not consumed enough carbohydrates, they would have had to generate glucose in other ways. However, glycosegenesis from non-carbohydrate sources would have meant massive energy loss, which could have affected hominin’s hunting efficiency, cognitive abilities and reproduction rates.6

- Many essential nutrients such as fibre, certain polyunsaturated fatty acids, some minerals and vitamins can only be supplied from plants and not from meat.6

Conclusion: The consumption of meat was most likely important for the evolution of the genus Homo. How important meat as a food actually was is controversial. How important meat was as a food is debatable. I am not a scientist and cannot give a serious assessment of these approaches. My aim was simply to show that the suggestion that meat was causally responsible for the development of the human brain is not a fact but a speculation (just as the extent to which carbohydrates are causally responsible can only be speculated).

The far more important point is that it doesn't matter which approach is right, as long as there is no evidence that eating meat is necessary for survival today, or that it is the only possible diet that meets our bodies' needs. So far, this evidence has not been forthcoming. On the contrary, more and more studies in the field of nutrition and health sciences are establishing a link between the consumption of animal products (especially meat) and the occurrence of certain diseases (e.g. cancer, cardiovascular diseases) and are emphasising that a vegan diet can have a positive effect on these diseases or even prevent them.[^mccarthy]

If it cannot be shown that an (informed) vegan diet is harmful to health or survival, it does not matter from an ethical point of view what helped our ancestors 2 million years ago to slowly evolve into the genus Homo.

Vegans are responsible for the deforestation of the rainforest

While there are different approaches and conclusions as to the extent to which intelligence, sentience or species membership are relevant criteria for granting moral rights, the soy argument has been clearly refuted. It is true that the immense cultivation of soy and corn leads to deforestation of the rainforest and to considerable environmental damage – but soy-eating vegans are not the main cause of this.

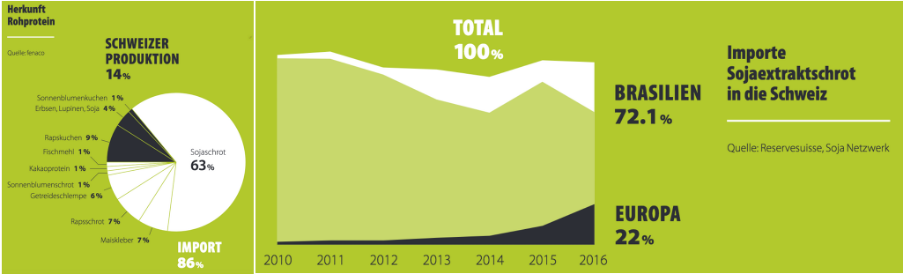

The fact is that most of the world's soy flour is used to feed farm animals. Switzerland, for example, produces 14% of its raw protein domestically, while the rest is imported. 68% of these imports are soy, of which 72.1% comes from Brazil. The reason why soy is so popular in animal feed is that its high protein and balanced amino acid content make it the perfect source of protein for animals.7

ETH Zurich professors Dr Michael Siegrist and Dr Christina Hartmann analysed a survey of 5586 participants from German- and French-speaking Switzerland on the environmental impact of meat. The study showed that participants mistakenly perceived the environmental impact of soy-based meat substitutes to be similar to that of conventionally produced beef. The authors conclude:

A rather surprising result was the participants’ perception of the environmental impact of soy-based meat substitutes as similar to that of conventionally produced meat. One possible explanation for this biased perception could be that soy production has been a major driver of deforestation in Brazil (Gollnow & Lakes, 2014).8 Therefore, consumers may associate all soy products, without differentiating between soy as food and soy as feed, with a negative environmental impact. This is a biased perception because soy used to feed animals for meat production causes a large environmental burden, but this is not the case of soy processed as plant protein for human consumption (Smetana, Mathys, Knoch, & Heinz, 2015).9 – Michael Siegrist and Christina Hartmann

The result can be summarised in two points:

1.) Soy production is one of the leading causes of rainforest deforestation. 2.) The largest demand for soy comes from the animal agricultre industry.

The consequences of intensive soy cultivation affects not only the environment, but also humans: People living in areas where soy is planted are forcibly displaced from their villages so that corporations can grow soy. But eating meat has even more devastating consequences for humanity. Pesticides are used to harvest soybeans at the lowest possible cost. This leads to excessive pollution of the environment, which in turn causes disease in the people who live there. Furthermore, it does not take a mathematician to calculate how many plant resources are used to feed animals that are later killed, which could otherwise be used to feed people suffering from hunger (not to mention the immense amount of water needed to raise animals).10 Opponents of veganism who imply that soy consumption is ethically reprehensible must, by their own logic, either stop eating meat altogether or limit it to the bare minimum. Only a small amount of soy is processed into products such as tofu, soy milk or meat substitutes, and soy used for human consumption does not come from Brazil, but - in the case of Switzerland - is produced domestically or imported from somewhere in Europe.11

Note: A vegan diet does not automatically mean a cruelty-free diet. Vegan products can still be produced in conditions that violate human rights or are particularly harmful to the environment. It is therefore important that we not only check whether a product is vegan or not, but also - as far as we can - whether the workers are employed under fair working conditions and receive a fair wage. For example, cocoa, which is used in non-vegan and many vegan chocolates, is often sourced through child labour, so it is important that we also find alternatives that respect human rights.

I only eat organic meat produced on farms where the animals could live happy lives

Happy cows, playful calves and free-range chickens - this is how we like to think of animal farming, especially organic farming. But does this image represent the truth? And even if it is, do we have the right to exploit and slaughter animals just because they have had a good life?

Let's start with the first point. Contrary to popular belief, animals raised on organic farms do not live in such idyllic conditions as those pictured above. It is true that organic farming has to follow stricter guidelines than conventional farming, but whether organic farming is ethically justifiable is another matter. A basic requirement for organic farms in Switzerland is to comply with the RAUS standard (Regelmässiger Auslauf im Freien aka Regular Outdoor Exercise).12 Organic farms therefore provide more space for the animals, but the minimum requirements are still low. For comparison: A pig living under conventional farming rules is allowed 0.9m2 of space to move around, while the minimum requirement according to Bio-Suisse is 1.65m2 (including space guaranteed for outdoor exercise).13

It is important to note that the association between organic farming and grazing is not always accurate. The requirement to allow animals to graze applies only to cattle and does not extend to other farm animals such as pigs, chickens, goats or sheep. The primary obligation for these animals is to provide them with access to an outdoor area. As a result, a significant number of animals are still housed in large barns. For example, in the case of organic laying hens, a maximum of two barn units per farm are allowed, with each unit housing up to 2,000 laying hens or 4,000 young hens. This means that organic eggs or chicken sold in regular supermarkets may come from sheds housing thousands of hens at a time.14

The issue of space alone is not decisive for being classified as organic. The organic food sector is also under pressure to make a profit. Even organically reared animals are used as a means to an end: they are genetically modified to produce more and are disposed of and replaced as soon as their performance starts to decline. In organic farming, calves are also torn from their mothers three months after birth (35 days for sheep and goats and 40 days for pigs) to be killed for veal.15 Organically reared animals live only a fraction of their natural lifespan: according to the Organic Farming Regulation, a chicken is slaughtered after 81 days, although it can live up to 10 years.16 Male chicks are still allowed to be killed (gassed or shredded) on their first day of life under organic labels because they are an unwanted by-product of the egg industry. In addition, the slaughter of animals is not protected by organic labels and most organically reared animals end up in the same slaughterhouse as conventionally reared animals.17

Anti-speciesists demand fundamental rights and/or fair consideration of the interests or preferences of animals. To have a basic moral right - such as the right to integrity or the right not to be killed for the benefit of others - means that it is wrong to deprive someone of that right, even if they have a "happy life"- Rights are a way of protecting the interests of others, and again they should not be violated, even if we could benefit from violating them. The reference to organic farming is not enough to explain why we can use animals as our property and breed, fatten, milk or slaughter them.

[^mccarthy] McCarty, M., Vegan Proteins May Reduce Risk of Cancer, Obesity, and Cardiovascular Disease by Promoting Increased Glucagon Activity, in: Medical Hypotheses, Bd. 53, Nr. 6, 1999, S. 459–485., Benatar, J., Stewart, R., Cardiometabolic Risk Factors and Plasma Fatty Acids in Vegans – Results of an Observational Study, in: Heart and Lung Circulation, Bd. 26, Nr. 2, 2007, S. 344.

- Kutschera, Ulrich, Evolutionsbiologie, Ursprung und Stammesentwicklung der Organismen, Stuttgart 2001.↩

- Mann, Neil J., A Brief History of Meat in the Human Diet and Current Health Implications, in: Meat Science, Bd. 144, 2018, S. 169 – 179.↩

- SRF, https://www.srf.ch/kultur/wissen/die-lust-auf-fleisch-machte-den-menschen-intelligent↩

- Mann, Neil. J., Omega-3 fatty acids in the Australian diet, in: Lipid Technology, Bd. 17, Nr. 4, 2005, S. 79 – 82.↩

- Hardy, Karen et al., The Importance of Dietary Carbohydrate in Human Evolution, in: The Quarterly Review of Biology,Bd. 90, Nr. 3, 2015, S. 252 – 268.↩

- Hardy, Karen, Plant Use in the Lower and Middle Palaeolithic, Food, Medicine and Raw Materials, in: Quaternary Science Reviews, Nr. 191, 2018, S. 393 – 405.↩

- Sojanetzwerk, https://www.sojanetzwerk.ch/fileadmin/user_upload/Downloads/soja-factsheet-de_170829_01.pdf↩

- Gollnow, F., Lakes, T., Policy Change, Land Use, and Agriculture: The Case of Soy Production and Catt↩

- Siegrist, Michael, Hartmann, Christina, Impact of Sustainability Perception on Consumption of Organic Meat and Meat Substitutes, in: Appetite, Bd. 132, 2019, S. 196 – 202.↩

- D'Silva, J., Webster, J., The Meat Crisis, Developing More Sustainable Production and Consumption, London 2010.↩

- Pichler, Renato, https://www.swissveg.ch/soja↩

- Naturschutz, http://naturschutz.ch/tipps/bio-ist-nicht-gleich-bio↩

- Bio-Suisse, https://www.bio-suisse.ch/media/de/pdf2010/landwirtschaft/inkraftsetzung/schweinehaltung_ver.pdf↩

- Bio-Suisse, https://www.bio-suisse.ch/media/Service/Produzenten/Inkraftsetzung/d_teil_ii_kap._5.5_gefluegelweisung_31.7.13.pdf↩

- Artikel 16b, 2, https://www.admin.ch/opc/de/classifiedcompilation/19970385/index.html↩

- Artikel 16g1 https://www.admin.ch/opc/de/classified-compilation/19970385/index.html#fn-#a15b-2↩

- Art. 3, f., https://www.admin.ch/opc/de/classified-compilation/19970385/index.html↩